Let’s start from a basic fact: the ‘Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris.’ They were present. And they made their presence visible, signing their statements during the May occupations as ‘Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris,’ leaving signs of their presence on the web, with pictures of their banners on the buildings they occupied, with flyers demanding support or calling a march, and with a few ironic images addressed to Europe. What all these ways of making one’s presence felt embody is indeed a depiction, the depiction of a presence during an action in space, a presence that occupies a space, that takes a space over, and a presence that, while announcing ‘who one is’ deliberately leaves marks of this being. But what would such a presence look like rendered as a cartographic representation?

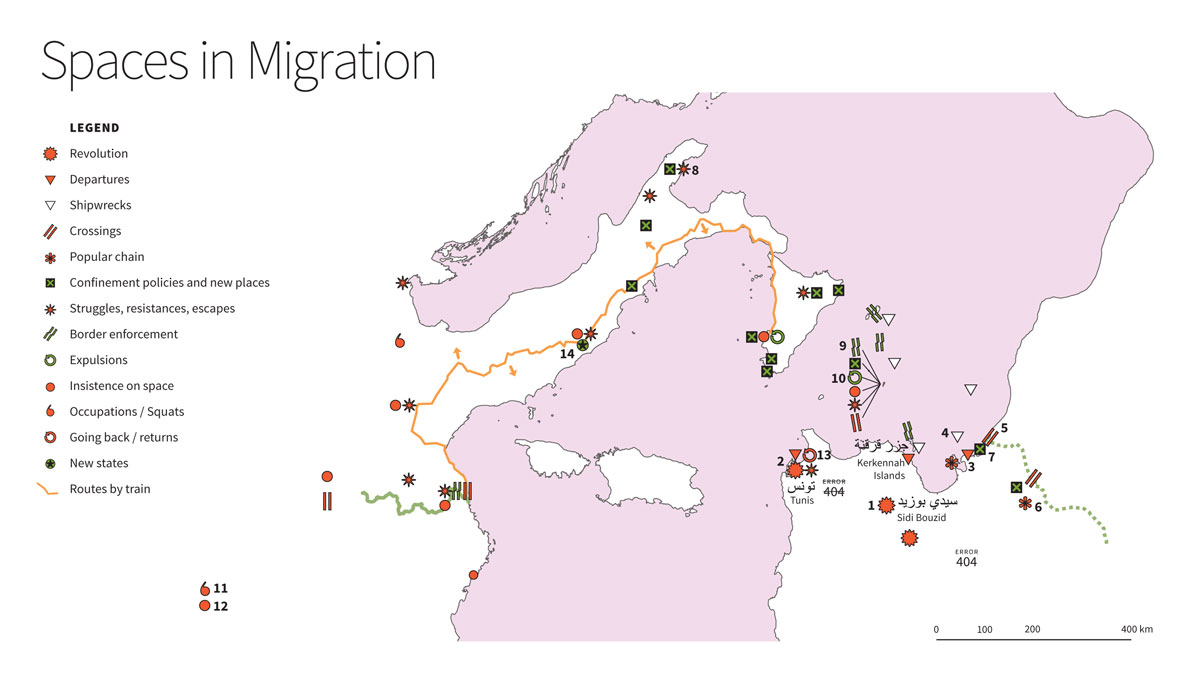

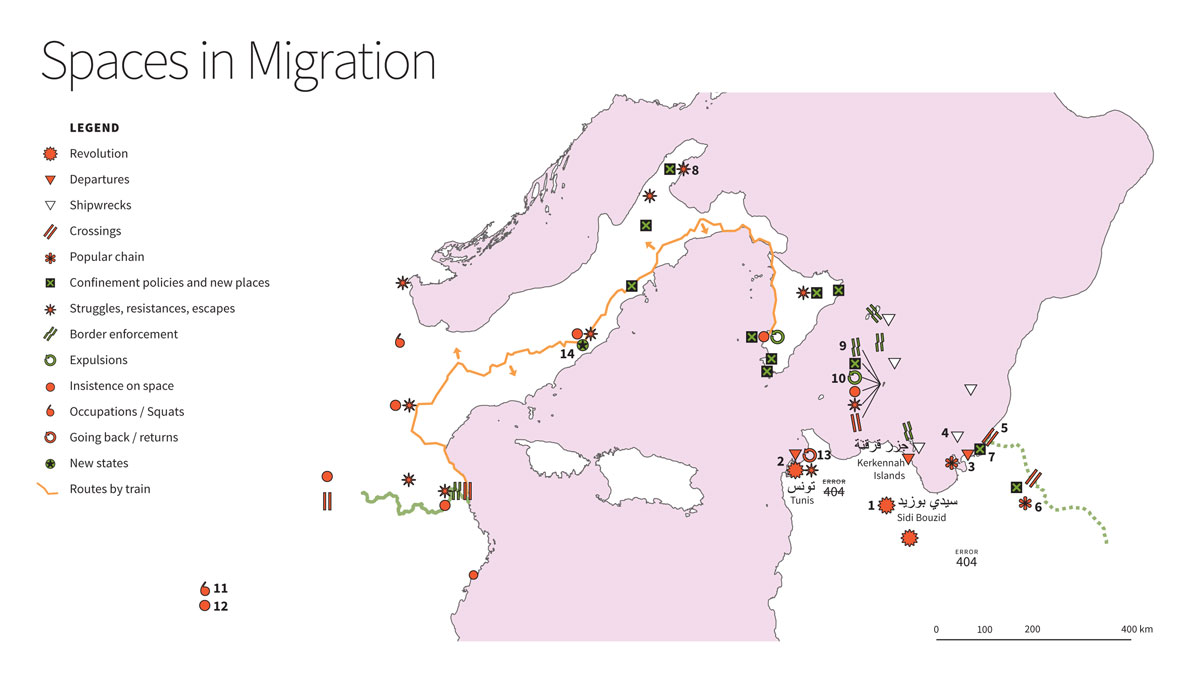

We are used to maps that depict states, cities, borders, seas and continents. And maps that politically rank such depictions. The eye sees and inscribes in its ‘memory’ the image of such a performed spatiality which is offered up in order to be internalized and propagated. We are used to maps that tell and perform events. Maps on migrations, for instance, in the past few years, have been performing ‘routes’ through the use of arrow marks to signal, in European newspapers and websites, an itinerary from the ‘rest’ of the world to European Union countries. In this way, not only are ‘routes’ performed, but they are performed unilaterally: from ‘elsewhere’ to ‘here,’ the ‘here’ denoting the location of the eye. There are also migration counter-maps that attempt to depict something else, which attempt to visualize what usually gets untold or omitted from mainstream verbal and visual narratives about migration policies, which journalists and researchers deploy, in their role as propagator of stories and visibility. In spite of ‘routes’ and ‘fluxes,’ counter-maps depict: migrants’ subjectivity, patrolling activities at sea, border controls in airports – by human and non human agents -, the death tolls. In these cases, the eye keeps looking but in order to actually see it needs to linger, to take its time: the time to actually see what usually one doesn’t see, the time to rid one’s perceptual schema of the memory of those arrows which harness migrations and which, in turn, harness the eye itself. But the eye also needs to take its time to understand these complicated depictions, wherein the ‘counter’ of counter-maps aims for visibility. A challenge to hegemonic visibility, in the attempt to posit a counter-visibility.

‘The Collective of Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris,’ however, posits endless problems to the sheer possibility of visibility itself, naming and ‘acting on’ a spatial unification. This unification is anarchic towards those perceptual and conceptual borders which have been inscribed in the grids of our eyes and minds by representations which span centuries. The Collective drags along states, continents, cities, islands, Europe, Africa, Tunisia, Italy, and France in a verbal anarchy which is acted out from within the buildings of its occupations. And, through its name, it suggests what indeed happened across the space of two continents in only a few months, continents which were separated by centuries of history, events, verbal and figural narratives, conceptualizations, as well as by a short stretch of sea. What was put in place was a sudden closeness and the bursting capacity, on the part of Tunisian migrants, to shake off the borders that migration policies inscribed onto their bodies, a capacity played by burning spatialities and temporalities, by causing the crisis not only of every possible spatial and temporal capture that these policies imply for migrants, but also the crisis of each figure or word that, despite its ‘counter,’ still aims to re-state and re-present them.

The map we present here is a challenge and a game. Or, to put it better, it is an attempt to spatially follow and imagine all the intricate tangles of that self-naming of ‘Collective of Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris,’ in the awareness that there always remains an un-depictable ‘rest’ in this necessity to follow that unexpected contestation of each possible existing depiction. No longer a question of states and borders but a space of events: revolutions, departures, crossings, popular chains, fights, resistances, flights, ‘insistences on space’, occupations and squats. Upheavals of bodies and existences, actions and words which burst into the spaces and the times of their captures, in squares and waters, finding themselves transposed in the course of a few days from the café Relais in Zarzis, to the train station ‘Quatre chemins’ in 168 cartographic games

Paris, bringing in an uncanny way Tunisia and its insurrection among the streets and the parks of France and of Europe. But the map also depicts those confinement policies, border enforcement and expulsion activities, the delirious prose conjuring up new states out of thin air, all these attempts to reinstate order, to hush bodies up, to counter-act their actions, to recover the usual narratives by inventing not only a counter-insurrectional prose but also spatial obstacles to the upheaval of Tunisian migrants. These attempts coincided with various Frontex engagements, endless summits, new sites of capture, a coming and going from one Mediterranean shore to the other, in the attempt to re-map that short stretch of sea as a distance hence giving France back to France, Italy back to Italy, and leaving a bit of Europe in the debris of new borders while leaving some islands to their extra-territorial destiny. And in-between lies the sea, unaware of its complicity, the words of a few survivors, and the huge silence of many others: many, very many Tunisian migrants and refugees fleeing the Libyan war, who perished while radar and satellite technologies, Frontex patrols and NATO helicopters, airplanes, ships hovered ‘contemplating’ the shipwrecks. Not at all a ‘shipwreck with spectator,’ the metaphor of a certain European conceptual and aesthetic tradition, but endless shipwrecks with far too many spectators.

What is the cartography of this upheaval then? The ‘game’ we propose is an exchange which demands a double exercise of the eye: look at images and read words, by turning space into the time of the narrative and turning the time of the narrative into space. A ‘game’ which responds to the attempt to follow that insubordinate remainder, insubordinate to spatialities and temporalities. Each icon on the map – the map of a unified space where the sea is more solid than the land and the land refuses to reproduce borders and attempts to transform itself into the land ‘of every woman and every man,’ where de-bordering practices took over cities and states turning them into gardens, parks, squats, tracks – corresponds to a ‘postcard,’ a narrative which composes an extended caption to the map which attempts to articulate what that strange insurrectional time of 2011 was. Allow us one last game: the attempt to ripple also chronological time, demanding that in gazing at the map the eye should imagine after-moments which are located beforehand, hence displacing itself from that ‘here’ in order to follow those after-moments whose presents, as events, escapes depiction and narration in the past tense.

March 15, 2012

Postcards : legend of the map

1. Revolution

A specific day marks the beginning of the Tunisian revolution: it is December 17, 2010, the day when Mohammed Bouazizi, a 26-year-old street vendor, sets himself on fire across the street from the local government building in the town of Sidi Bouzid, after Tunisian authorities confiscated the merchandise he was selling. Actually, there is a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ framing the acts of immolation that have characterized the Tunisian revolution. Prior to December 17, 2010 two young Tunisian men set themselves on fire on March 3, 2010 in Monastir and on November 20, in Metlaoui. Afterwards, on December 22, 2010, another immolation follows Mohammed Bouazizi’s in Sidi Bouzid: it is the immolation of Houcine Nejji, a young unemployed Tunisian, who commits suicide hanging himself from electric wires. Just a few days later, on December 26, a young Tunisian throws himself in a well, again in Sidi Bouzid. This revolution starts from the cities of central Tunisia: Kasserine, Gafsa, Menzel Bouzaiane, Sidi Bouzid, Merknassy. In the first few days, the revolution is concentrated inside Tunisia, where popular insurrections continue to multiply: on December 27, 2010, protests extend to Gafsa and Kasserine where people march in the main squares with scuffles occurring; but protests also extend out to the coast – reaching the cities of Gabès and Sousse – and also Tunis. On January 4, 2011, Mohammed Bouazizi dies and his funeral, marked on January 5, becomes the icon of the revolution.

In terms of triggers of the revolution, commentators point to the high unemployment rate, especially among young people and the lack of socio-economic opportunities associated with a dire increase in the cost of basic necessities. But already during these first days, protesters target symbols of Ben Ali’s regime, the offices and headquarters of the RCD (the regime party), setting police stations on fire that, besides representing the repressive arm of power, are also emblematic of its corruption. On January 30, riots reached Monastir, where police react violently against citizens who have taken to the square to protest against unemployment and the high cost of living.

To accurately provide an account of the ‘before’ of the revolution one should look back to 2008, to the riots and strikes of Gafsa mine workers when police repression resulted in bloody confrontations and two people died. These riots started to produce fissures in the structures of power, following the bloody repression of student protests in 1974 and the ‘bread riots’ of 1984.

On December 24, 2010 two young male protesters are killed in Menzel Bouzaian. They are the first two victims of the violent repression of the marches. A political response to these events won’t happen until December 28, when Ben Ali gives an ambiguous speech, stating on the one hand that he will take protesters’ claims into account but also stating that those who are protesting are just a small group of ‘extremist activists.’

On January 10, the President gives a second speech promising 300,000 jobs within a short period of time and, at the same time, condemning the uprisings as ‘terrorist acts.’ Ben Ali’s speech is delivered following two days of repressive action against protesters. Across the country, violent clashes between protesters and law enforcement agents increase and 14 civilians are killed in Kasserine, Thala and Regueb.

But already during this first stage, the revolution unfolds through networks and self-organized movements, going beyond single isolated acts or head-on confrontations between protestors and police. In Sidi Bouzid, for instance, teachers and professors form the ‘Marginals’ Committee,’ a protest coordinating unit, supported by the main Tunisian union, the UGTT. In Kasserine, it is the lawyers who, for five days starting from December 24, protest putting pressure on the UGTT to fully support the ongoing struggles. The law- yers’ movement reaches its peak on January 6, 2011 when the profession launches a general strike. On January 3, when schools re-open after the winter break, students from middle schools also join the protests. Even the UGTT assumes a more radical position, after the increasingly violent police repressions during the first week of January (particularly in Kasserine): stepping out of the mediating role between revolutionary forces and regime’s powers, now the UGTT is unambiguously on the side of the protests’ claims. The change is also partially driven by internal tensions as the faction closer to the Tunisian Communist Party takes the lead in the union movement at a local level, taking part in the protests. In the meantime, immolation acts continue: on January 8, again in Sidi Bouzid, a 50-year old business owner sets himself on fire in the main square and, two days later in the same spot, a young graduate commits suicide publicly. On January 14, when Ben Ali is ousted from Tunis, a series of protests and clashes take place across the country and particularly in Sfax, Thala and Douz, where two protesters die. Clashes and riots continue throughout the country in the days which follow. On Janaury 17, in Sfax and Sousse, Tunisian citizens vehemently contest the newly formed national unity government, for the presence of many politicians from Ben Ali’s RCD. The revolutionary fervor continues way beyond January 14, which is being labeled in Europe as the Arab peoples’ storming of the Bastille. During the month of August riots start again in the south of Tunisia and in Gabès. As a response, on September 6, the provisional government proclaims a state of national emergency. And the revolution does not cease even with the October 23, 2011 elections, in which the victory of the Islamist party Ennhada is declared, because, beyond these institutional figures, the terrain of ‘political society’ remains to be defined.

2. Revolution.

As was the case with the previous postcard from Sidi Bouzid, for this postcard events also revolve around a precise day: January 14, 2011, the day of Ben Ali’s escape. However, reading accounts of the revolution one can observe that, in fact, in Tunis protests started before the 14th and went beyond that day as well. Moreover, turning our gaze to other crucial episodes happening in Tunis we might explore alternatives to that mainstream narrative depicting ‘Arab Springs’ as the awakening of a civil society calling for representative democracy – an account inscribing revolutionary movements into the predetermined path leading towards a political form already accomplished in the countries of the Northern shore of the Mediterranean.

Protests open in the capital with a march comprising about 1,000 people. The march is called in solidarity with the events of Sidi Bouzid and with the lawyers’ movement who organized a sit-in across the Interior Ministry from December 27 to 31, 2010. On January 10, the day when in the rest of the country protests as well as police repressions reach boiling point, the capital is hit by violent clashes around the city’s peripheries and students protest outside El Manar University which gets quickly hemmed in by the police. Ben Ali makes a last ditch attempt to stop this wave of protests which is attended so widely (by students, lawyers, teachers and professors, young unemployed people) and unfolding across the whole country: on January 12, 2011 the regime announces the liberation of all people arrested during the riots; on January 13, in his last speech, Ben Ali proclaims the freedom of the press, the end of internet censorship, and the lowering of the prices of a few food products; he also orders the police not to shoot protesters and declares that he will not run in the next elections. These promises are worth nothing in the face of an insurrection that has expanded and that the next day invades the streets of Tunis until Ben Ali is forced to leave the country. The police answer suppressing contestations that, on January 14, traverse the entire city, while the army starts to protect protesters against the police.

To defend the revolution, the next day, popular committees are formed to protect Tunis’ neighborhoods. During the night, between January 13 and 14, another icon of Ben Ali’s regime comes to an end: ‘erreur 404,’ the script that tended to pop up on the screen on try- ing to access censored Internet pages. Censorship is banned from many internet sites, including Youtube and Dailymotion and, while during its early stages images of the revolution managed to circulate in one way or another on the web, starting from this day the use of the Internet as the tool spreading the revolutionary movement and as the means of attracting support for protests takes on a larger role. A revolution of the Internet and through the Internet: the central role of the web has been to create proximity between the spaces inside Tunisia and the spaces outside it and to create real – not virtual – spaces for practices of resistance. One example, among others, is ZarzisTv, the web tv started by young people in the costal city of Zarzis and which by circulating images of the sites where the first protests were happening, contributed to the spread of insurrections across the extreme southern tip of Tunisia.

However, the revolutionary impetus did not fade with Ben Ali’s escape. In fact, just three days after his flight, people take to the streets and gather in the squares again in protest against the composition of the transitional government restaging the presence of RCD ministries and which is led by Mohammed Gannouchi. On the same day, Gannouchi announces the liberation of all those imprisoned for their political views and declares freedom of information. Protests continue on January 22, on the eve of the first Kasbah, a sit-in in the square of the government seat aimed at overthrowing the interim government.

An alternative narrative of the revolution to the one that media and political commentators from the Northern shore of the Mediterranean circulated would read the two Kasbahs (January 23 and February 22, 2011) as two climaxes of the radicalization of the movement, moments that the discourse and the categories of representative democracy – the frames within which the ‘Arab Springs’ have to some extent been confined – can’t quite grasp. On January 27, 2011 the first minister Mohammed Gannouchi announces the formation of a new government and the next day the square is forcefully cleared out by police. During the second Kasbah (22-25 February), when protesters demanded Gannouchi’s resignation and the formation of a constituent assembly, the police kill two people. Yet, following Gannouchi’s resignation, protests and contestations still continue on several occasions.

3. Departures

It is impossible to trace the exact moment when Tunisian migrants started to leave towards Europe, without looking at the arrivals in Italy. But in order to reconstruct the long chronology of departures it is necessary to also look at the other shore and to pay attention to interceptions at sea on the part of Italian authorities. At Lampedusa Island, the first arrivals are already documented on Janaury 15, 2011, the day after the fall and flight of Ben Ali. They consist of a group of 100 people. On January 19, 2011, more people arrive at Pantelleria, Lampedusa, and Marsala. From the month of February onwards, departures become more frequent, often taking place in broad daylight, and from various areas of the Tunisian shoreline, namely small piers, beaches, and cities. Zarzis, in southern Tunisia, is the city where most people depart from. For this reason this postcard ‘Departures’ is sent from Zarzis, via the icon and the number that, from the map, lead to this. At first it is mainly young people from the city of Zarzis leaving; then also young people from other villages and cities from further inland. Between February 10 and 11, 1,100 migrants arrive at Lampedusa Island from Tunisia. Their arrival spurs controversy in Italy and throughout Europe. But the questioning around their departures starts on the other side of the Mediterranean, cutting across the entire Tunisian society and involving people from the places where most departures are occurring, comprising various insinuations of a betrayal of the revolution on the part of those who were leaving. It is indeed possible that among those who left first there may have been also people who were too compromised by the former regime to remain in Tunisia after the revolution. Where are they now? Ru- mour has it that they may have received refugee status, that they may have resettled in other European countries, and that they left Tuni- sia via safe crossing which brought them to very different places to Lampedusa Island. The other open question is: why did enforcement authorities allow all these departures to happen? What was the interest motivating this? The image of open borders due to the absence of police authorities in those days, i.e., the simplified image that circulated in Europe, quickly dissolves with further investigation, going to Tunisian coffee shops and paying attention to the assumptions that circulate among those who witnessed the events. Doubts and open questions persist – even if, in some interviews with the Garde Nationale Maritime we are shown clips of a sort of reverse ‘clandestinity’ featuring Garde Nationale ships, some even donated by Italy, approaching – albeit maintaining a distance – migrants on boats to tell them to turn back or, to be more precise, suggesting turning back in order not to risk their lives. In one bit of footage we saw, a corpse was laying on a guard ship and the guards were pointing at him, ‘pleading with’ the young men en route to Europe not to run the same risk. The day before our interviews with the Garde Nationale, at the pier in Zarzis, some young men told us how migrant boats were being approached: ‘the Garde Nationale comes close and they ask us who wants to proceed with the trip and who wants to turn back. Who decides to return may board on the guard ship while the others continue the trip.’ We took this as a joke and we made fun of them for this description but after interviewing the ‘guardians’ of the shores and of the sea we realized that there was no joke here. The phenomenon of departures, however, quickly reaches a peak and the controversy around supposed betrayal becomes ludicrous. It in fact becomes clear that there is way more at stake in people’s decision to depart. Some union members in Zarzis stop talking about the betrayal of departees in order to prevent being called traitors themselves, someone who betrays by failing to understand the desire and the necessity behind those trips. People leave from Zarzis, Djerba, Gabes, Sfax, Mahdia, Monastir, Sousse, and Tunis. Or from the beaches of Sidi Mansour, Luza, El Kram, Chebba, El Haouria, Kelibia, and Ghar el Melhe, which are monitored less than the piers. During the entire month of March 2011, the entire Tunisian coast was taken up with preparation and departures. To give an example, we can offer data reconstruct- ed by ‘hearsay’ coming from the parents of missing migrants: on March 14, 2011 five boats leave from the beaches around Sfax. Three shipwrecks are reported for that night. Estimates for departures from Zarzis reach 5,000 young residents of a city with a population of 71,000 inhabitants. Among them, a few women, who, according to the stories we listened to during the following months, were wives of Tunisians already residing in countries of the European Union returning to Tunisia to fast-track a family ‘reunion,’ with this trip across the sea. So people left, and left, and left. But because documentation of these departures would be required simultaneously at all the points of embarkation, we are forced to instead talk about them in terms of arrivals, if not shipwrecks or push-back operations. On April 7, 2011, two days after Italy reached an agreement with Tunisia on the repatriation of migrants, the Interior Minister Roberto Maroni, refers the following data to the Chamber: ‘With regards to the situation of arrivals on the Italian shores, I report that from January 1 to April 6, 2011, 390 landings took place, coinciding with a total of 25,867 people; 23,352 people arrived at the Pelagie islands; among those, 21,519 claimed to be Tunisians and coming from a precise area in Tunisia, namely the southern area, exactly from the piers of Djerba and Zarzis, which up until the end of last year used to be patrolled by the Tunisian police and to prevent the departure of those Tunisian citizens already boarded. However, starting from the beginning of 2012, these police authorities are not there anymore.’ Trips continue, even after the repatriation agreement. There are a few breaks due to weather conditions, to news about repatriations that quickly circulate in Tunisia, or to some symbolic arrests that Tunisian authorities perform in their territorial waters. On April 7, 190 migrants are intercepted and are immediately summoned before a judge. On June 13, the Italian Interior Ministry provides new data on migrants’ arrivals, speaking of a continuation of the trips towards Europe even if these occur at a slower pace than in previous months. Between the Spring and Summer of 2012, migrants coming from Libya substitute those from Tunisia at Lampedusa island. 42,807 migrants ar- rived in Italy during the first 5 months of 2011; among them, 24,356 were from Tunisia, 4,175 from Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia; 1,680 from Nigeria; 1,134 from Mali; 827 from Bangladesh; 761 from Egypt; 730 from the Ivory Coast; 713 from Afghanistan; and 530 from Pakistan. What stops departures, at least the departures which had been characterizing the ‘Spring and Summer of Tunsian migrants,’ is the episode of the boats used as identification and expulsion centers in the pier of Palermo, where Tunisian migrants were sequestered aboard so that authorities could proceed to repatriations directly from Palermo airport. This happens in the last week of September, after the burning of the detention center in Lampedusa, and in the aftermath of the ‘lynching’ of Tunisians by some of the island’s residents, in which the law enforcement agents failed to intervene, caught up as they were in their duties of repression.

4. Shipwrecks

Let’s start once more from an ‘impossibility.’ While tallies have been kept and statistics proffered, all these numbers surely can’t be more than hypothesis given the high number of undocumented shipwrecks. Some statistics indicate about 1,500 deaths in the Sicilian channel during 2011 for those who left Tunisia and Libya, whereas FortressEurope reports of 1,822 deaths, and a third source puts the total at about 2,000 deaths.1

Perhaps it is necessary to move away from the sea and onto the land, to look at the cemeteries and mortuaries of both site of de- parture and non-arrival. But all this would confirm is that the numbers of buried and unburied corpses remains unknown. On April 1, 2011, Tunisian authorities report the discovery of the bodies of 27 young men in the waters surrounding the island of Kerkennah. The men had left on March 13, March 27, and May 11, 2011. Authorities also announce that 58 corpses have been found on Tunisian beaches during April 2011.

Still, in the attempt to count shipwrecks, one could remain at sea, focusing less on those missing and more on those who caused them to disappear. Here, one is spoilt for choice over which news and data to look at: the endless fights between Italy and Malta about which pier has the competence to deal with boats adrift? Or Italy and Malta’s long-standing bickering over the SAR (search and rescue) zone which achieved a new level of intensity during ‘the year of the deaths’? On April 12, 2011 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) demands that the European Union urgently put in place more effective mechanisms to rescue people in trouble at sea. ‘A longstanding tradition of saving lives at sea may be at risk if it becomes an issue of contention between states as to who rescues whom,’ declares Erika Feller, Assistant High Commissioner for Protection. The ‘typo’ accurately describes the situation: Italy and Malta’s fight, in fact, is not about ‘who should rescue whom’; it is about who might not-rescue whom.

But this longstanding tradition of saving lives had anyway already been compromised many times during previous years, with boats left adrift with survivors’ bodies hanging on to tuna fish cages for days. However, should one stop at those fights, one would overlook the work of the agency Frontex and its ‘interceptions’ – most often a euphemism for push-back operations – and tactics of ‘dissuasion’ – another euphemism to define the practices relied on by the agency in the waters belonging to the migrants’ countries of origin, in this case those of Libya and Tunisia. Furthermore, to focus exclusively on the quarrel between Italy and Malta, would reduce 2011 to obliv- ion, overlooking those NATO forces – boats, helicopters, airplanes – enlisted to ‘defend’ the Libyan population in the war carried out by the Coalition of the willing, while part of that very population (taking residents, not just citizens into account) was fleeing the war by sea,‘uncontestedly’ shipwrecking in front of indifferent crews. While these are often overlooked or forgotten, there are two definitive dates that are worth noting. The first lasts for days on end, the second one comprises an instant. Sixteen days were spent adrift in March 2011 by a group of migrants who left from Libya on a boat spotted by NATO forces who subsequently omitted to rescue it, letting most of its passengers, 72 people, die ‘of sea’, of sun, of hunger, and of thirst. On May 8, 2011 – the second date of this account – the newspaper The Guardian reports the news, following coverage from less prominent news sources and websites in previous days.

But let’s stick to shipwrecks only, in isolation from the context and from those who cause them. In the Metline shipwreck, a few kilometers from Tunis, a young boy dies. On February 11, 2011, while statistics about arrivals to date and future projections are blasted around Italy, Tunisia is being asked to stop departures. A Tunisian military boat rams the boat ‘Raïes Ali 2’, causing the death of 5 peo- ple and the disappearance of 30 others. In the days that follow, as survivors started blaming Tunisian militaries, the Navy ‘gets to work’ on the episode to archive it as an ‘accident’ for which migrants are pointed to as responsible. It is after this ‘Raïes Ali 2’ episode that we designate the icon Shipwreck.

A few days after this, Italy goes as far as to open fire on Egyptian migrants in the waters off Ragusa, Sicily, and one person gets injured. In the following days a long series of deaths. An unknown number of deaths for the March 13 and 27 2011 shipwrecks in the waters off Sfax and for April 3, one off the Libyan coast, On April 6, 2011, close to Malta, only 47 survive out of 200 people. Unknown numbers of deaths for the April 28 shipwreck off the Libyan coast. Almost 40 people died and disappeared off Libya on May 6, 2011; possibly 300 people ‘disappeared’ off the Kerkennah Islands on July 2, 2011. It is at this precise moment that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) launches a warning. According to estimates based on survivor accounts, 1,500 migrants died attempting to reach Europe from Libya and Tunisia in the course of just two months, UNHCR declares. And the list goes on. On August 1, 2011, 25 people are found dead in the hold of a fishing boat landing at Lampedusa island. On August 8, 30 people or more are found dead on a boat rescued off Lampedusa waters. The list continues as one keeps looking out to sea but this time with feet firmly on dry land. On August 4, 2011 Italian newspapers disclose an unconfirmed story. Italian authorities allegedly informed a NATO boat about a drifting ship in need of rescue before the Costal Guard of Lampedusa could intervene. NATO refused to intervene. ‘If confirmed,’ the Italian Foreign Affairs Minister said, ‘this would be a very serious piece of news.’

During the course of the day the story is indeed partially confirmed. It is confirmed that the former Italian minister Maroni request- ed NATO’s intervention. However, it turns out that this was not a request to rescue the boat but, rather, a request to send it back. ‘It is a priority that, to meet the mandate it received, NATO should stop and push back boats to the point of departure in order to avoid all these deaths we have been witnessing,’ is the ‘human’ discourse proclaimed by Maroni, who goes on to declare that ‘NATO forces can’t close their eyes and ignore the fact that they are there to protect civilians. This is a task NATO can’t shirk.’ Indeed, European policies have long been preoccupied with their focus on the ‘all too human’, at least since 2006, when the EU border agency started to intervene with ‘dissuasion’/ ‘deterrence’ missions, predicated on ever-growing statistics about deaths in the Atlantic Ocean between Senegal and

the Canary Islands. Returning to 2011 now and specifically to August 5 2011. Survivors of this NATO ‘not rescued-pushed back’ boat provide further information through their conversations with Doctors Without Borders. About a hundred people died on that boat and their bodies were thrown in the water.

5. Crossings

As hard as it is to count those who died, it is equally hard to count those migrants who managed to arrive safely. Based on the idea of chronology, we should indicate the icon Crossings as originating from the place where the first passages took place across a state bor- ders. Should we choose to follow this chronology, this would be the Island of Lampedusa, as crossed ‘frontier’. However, this account risks unwittingly affirming the dominant European narrative. In order to turn this narrative upside-down, it is also necessary to turn temporal coordinates upside-down, hence starting the narrative from a ‘subsequent’ moment in order to make visible that space which, for a few months, saw the arrival and departure of people, cars, objects, food, and flags: a space of pure crossing, devoid of ‘frontiers’ despite the fact that this space marks the border between states as well. It is the space of Ajdir and Dehiba, in the Tunisian desert at the border with Libya. These are the spaces from whence we want to start this story of crossings because it is here that millions of people converged, already in February 2011, when the Tunisian revolution began to extend to squares and cities in other Maghreb and Mashreq countries. At first people were fleeing Gaddafi’s repression and then they were fleeing the ‘joint’ bombing by the Colonel’s Army and the NATO Coalition of the Willing. These were migrants from many African and Asian countries, who, for over a decade, had constituted the ‘workers army’ of Gaddafi’s Libya. And some of these migrants from African countries were already fleeing their countries of origin, who, while transiting in Libya en route to Europe had been stalled there because of the waiting times EU migration government policies and the Friendship agreement between Italy and the Colonel imposed upon them.

Tunisia kept the border with Libya open all the time, except for a few days when the confrontations between Libyan rebels and the forces loyal to Gaddafi moved to the borderline. This postcard of Crossings features images of women, men, and children: carrying packages, driving cars, transporting oil tanks, food provisions, or even nothing. After Gaddafi’s fall in August 2011, this crossing turned into a counter-crossing, which witnessed Libyan families outnumbering Tunisian militaries at the border: families crossing back home, honking their cars, flying flags, gesturing the victory sign or even kissing the ground at the moment of entry into Libya. How many have crossed since February 2011? Hundreds of thousands people, who re-revolutionized the Tunisian space, especially in the South where Tunisian men and women were making space and making space also for them, those people fleeing Libya, hence giving another lesson to the entire world, even if part of the world constrained itself to the misery of a gaze, blinded by the incapacity to see beyond itself. This making space for people fleeing Libya consisted in the activity of popular committees, the young and not-so-young returning from the experience of the Kasba in Tunis, Facebook pages and radio messages to find houses, rooms to stay, and beds or mattresses, from Tunisia to the enlarged Tunisia of migrants or of Tunisian exiles all across the world. This was the spontaneous space-making that happened in Tunisia and that was so different from the space made by humanitarian operators, with their tents and their humanitarian kits aimed at ‘humanitarian’ – and not human – lives. This crossing away from repression, war, and bombings, has been photographed by a war of numbers, which were either testimony to the competences of different organizations – such as the repatriation flights organized by the International Organization of Migrations, or the management of tent camps by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or by Tunisian Half Moons or by national or international Red Cross – or to glorify one’s generosity, as in the case of the revolutionary committees or of the Tunisian government itself. Numbers vary between 300,000 to 1 million, depending on who, amongst those actors indicated above, provides them and according to the ways in which the lives crossing kept organizing their autonomous space of crossing. At times, in fact, people were coming and going, especially Libyan men who were often crossing back across the border to join the rebel forces having made their families safe in some city, village, house or hotel in Southern Tunisia.

Other crossings, if one considers the ‘border’ in a traditional sense, are those of Tunisian migrants with their departures towards Europe. Lampedusa is their first step onto European soil. Ventimiglia constitutes the way to reach a Europe different to an encampment or detention centre. Or it did, at least up until the Italy-Tunisia agreements mandated the repatriation for all Tunisians who had arrived after April 5, 2011 and, for those who had arrived by that date, the residence permit and the travel document for the Schengen zone, a ‘valid-not-valid’ permit depending on whose indications one decides to follow – i.e., the Italian, French, the EU Home Affairs Minister or Commissioner. Finally, a third crossing practice is registered towards Switzerland, when it becomes clear that, by filing an asylum claim, it is possible to stay put for a few months. But in all these cases, traditional ‘borders’ dissolve, as is always the case when migrants are in the act of crossing them, especially in this case when they were burned not only by the rapidity of the crossing but also by the demand and the certainty in this crossing. It would be pointless to designate the crossing icon in these crossed-not-crossed spaces, where an island is already Europe – albeit European policies rushed its transformation into a camp or segregation site; it would be pointless to designate this at Ventimiliga because, despite the re-establishment of borders that took place there, Lampedusa was already Ventimiglia, was already France, Paris, Brussels, Berlin, in a unification of spatial practices where Europe rediscovered itself as Tunisia or, more clear- ly put, Europe found itself equally shaken up by the Tunisian ‘Spring.’

6. Popular Chain

It was a slap in the face for the humanitarian government – referred to, in fact, as a gifle tunisienne – enacted by a portion of the Tunisian population when, as early as March 2011, it ‘made space’ for Libyans crossing the border with Tunisia in order to flee the war. A temporal slap in the face, as the popular chain started well before the arrival of ‘humanitarian agencies’ such as the UNHCR. But it has also been a slap in the face in terms of the way reception was practised. The hospitality provided was not that of an ‘idle governmentality’ over life or the issue of standardized humanitarian kits: it was a full reception that also took people’s everyday needs into account. An emergency government over lives versus an ordinary government of existences, a human chain versus a humanitarian chain, so to speak, the former anticipating the latter but then finding itself coexisting alongside it, partly resisting it and partly finding itself captured by it.

The popular chain which started in March 2011 in Tataouine – an inland city in the eponymous desert situated 60 kilometers from the Dehiba border – made space for thousands of families from Libya. These reception practices were initiated by popular committees as a means of defending the revolution in the aftermath of Ben Ali’s fall so as to prevent the revolutionary process being recuperated by political forces close to or in continuity with the forces of the regime.

It is a popular chain that becomes even more relevant in this story if one considers that Tataouine is not the only region where this practice of making space for Libyans emerged; for instance, on Djerba island, a human chain very similar to Tataouine’s was activated. However, it is in Tataouine that almost 90% of Libyans were hosted by Tunisian families while others sought accommodations in hotels, also contributing to the compensation of economic losses that Tunisia incurred since 2011 due to the steady decrease in tourism. In Tataouine, the popular network provided accommodation and food; and when the Tataouine committees circulated the news about thousands of people from Libya on the territory, citizens of other Tunisian regions mobilized with substantial contributions, responding to the appeal launched to host Libyans from all across Tunisia.

According to estimates from the Committees, about 60,000 Libyans found a place in Tataouine, doubling its resident population. Also in Djerba a similar scale phenomenon occurred: the 100,000 resident population grew by another 100,000 people, i.e., the Libyans who found refuge in Djerba, from April to June 2011; in the same period, eighty flights a day would leave Djerba airport to repatriate third-country nationals fleeing Libya.

However this popular chain, or, more precisely, this series of popular chains, stopped when people arriving from Libya were not Libyans anymore but ‘Africans,’ as Tunisians call them, i.e., Libyan residents mainly coming from sub-Saharan countries. Their presences could only find a place in the camps installed by humanitarian agencies: in Choucha, six kilometres from the Ras Ajdir border, with 22,000 in March 2011; in other camps in the vicinity run by Qatar and United Arab Emirates; or in the camp of Remada, towards the Dehiba border.

These complexities and ambiguities characteristic of the Tunisian popular movement can also be traced through its relationship with the humanitarian chain: the two chains – the spontaneous popular chain and the chain of humanitarian organizations – coexisted since April 2011 in the border-space of Tataouine, This coexistence was marked on the one hand by the role that the popular chain played as a source of local resistances and as a force of friction against the emergency logic deployed by the UNHCR in handling the situation. On the other hand, however, this aide populaire (popular assistance) allowed itself to become co-opted by the government of the humanitarian: the UNHCR ended up gaining from the popular chain, using it to get direct contact with Libyan families. Moreover, the European Union, when interpreting the outcomes of the Arab Springs using the discourse of crisis, adopted the Tunisian model and promoted ‘the formation of grass root communities to assist asylum seekers.’ While Italy, faced with the arrival of 250,000 Tunisian migrants deported those who arrived after April 5 and released a temporary residence permit to those arriving earlier in the hope that they would cross over into France, and while France carried out its own interpretation of Schengen policy preventing the entry of Tunisian migrants into France, the country of Tunisia instead hosted 600,000 Libyans displaced by the war. In the tents of Choucha, however, thousands of non-Libyans were blocked and stranded by humanitarian forces while waiting to be resettled with no popular chain set in motion for them.

7. Confinement Policies and New Places

Upheavals associated with the Arab revolutions are matched by an increase in the number of places and policies of confinement on both shores of the Mediterranean. Our mapping of this series starts from Choucha camp in Tunisia, 7 kilometers from the border with Libya, close to Ras Ajdir. This is a camp opened by the UNHCR on February 23, 2011. Thousands and thousands of people fleeing Libya were assisted in this expanse of tents, peaking at 22,000 on March 22, 2011. A transit camp turned into a parking camp for asylum seekers and refugees, which also became a death camp. In fact, after refugees blocked the road leading to Libya demanding the procedures for resettlement be sped up, some people from Ben Guardane organized a raid during the night of May 23 causing the death of four Eri- trean citizens and harming twelve refugees. Choucha also functions as a suspension camp where one doesn’t know what will happen but simply waits to be ‘resettled’ to a sort of imaginary ‘elsewhere’ which is unlikely to be Europe and hardly Canada or the United States, to name the resettlement places the UNHCR hinted at when ‘distilling’ refuge as part of its humanitarian system.

At the beginning of March 2012 more than 3,000 people dreamt of their ‘elsewhere’ from the tents of Choucha. Between February and March 2011, when the Libyan rebellion against Gaddafi started and then during NATO’s war waged ‘in defense’ of the civilian population, five more camps opened in Tunisia, along the two border zones with Libya: Ras Ajdir and Dehiba. United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Western humanitarian operations already being run elsewhere deployed overlapping governmental technologies for fleeing populations. In deploying these technologies, these forces were assuring their future interests in the region, on both sides of the border, once the war came to an end.

In the meantime, at Lampedusa, temporary accommodations were improvised for Tunisians who started arriving towards the end of January 2011: the dock, the beach, the empty summer houses, tent camps made of cellophane or plastic bags. Confinement to the nth degree. The governmental delay in processing migrant transfers to the rest of the Italian territory provoked a forced confinement for Tunisian migrants and Lampedusa residents, a confinement which was all-too-easily seized by the media in its reports of the island’s invasion by migrants.

On February 14, 2011, Italian Interior Minister Roberto Maroni, reopened the first aid and assistance center (Centro di primo soccorso e accoglienza, CPSA) of Contrada Imbriacola for adult males and the ‘Loran’ former military base for unaccompanied minors and ‘vulnerable subjects’ – after he had talked for days of an emergency originating from what he termed ‘the fall of the Maghreb wall.’

But in Lampedusa it was not a welcome reception but detention that was offered to migrants. In the former military base of ‘Loran,’ minors were detained and the Contrada Imbriacola center became the site of collective expulsions – Contrada Imbriacola had served as a detention center in the past and was subsequently turned into a CPSA (first aid and assistance center), before this last transformation into detention and expulsion center. It will definitively close at the end of the summer of 2011, set on fire by migrants rioting against their seizure and against the announcement of new repatriations, while the island is declared an ‘unsafe haven’ after residents and police forces assaulted Tunisian migrants on September 21, 2011.

If Lampedusa was presented as camp-island under invasion, the center for asylum seekers of Mineo, in the province of Catania, was instead presented in terms of the ‘made in Italy’ model of European reception. Inaugurated on March 18, 2011, in the ‘Villaggio degli Aranci’ (Oranges Village), the center comprises a complex originally build for the U.S. Military Navy of the Sigonella aereonaval station – the builder, the Pizzarotti company from Parma, followed the ‘gated community’ model when planning the 404 houses of the village. With a capacity for hosting 2,000 people, the complex was reconverted into a ‘Solidarity Village’ and managed first by the Red Cross and subsequently by the cooperative Sisifo, with governmental funding of 40 Euros a day provided for each asylum seeker. This ‘golden prison’ was actually the site of multiple forms of confinement for its ‘inhabitants’: geographic isolation, food poisoning, lack of cultural mediation programs, slowness in the review of the asylum claims, absence of programs to manage the second stage of refugees’ reception after their exit from the center. The center hosted not only asylum claimants just arrived at Lampedusa but also those who had arrived years earlier, were living in other Italian centers, and ended up being uprooted and forced to start the whole process from scratch. As a refugee center, Mineo is indeed a 3 million Euros a month business and in fact the bid for tender became an undignified scramble.

Among the new sites for ‘reception,’ it is also worth mentioning the tent encampment of Manduria, in the province of Taranto, which opened on March 28, 2011. Manudria is the first of a series of temporary identification and expulsion centers that emerged in Italy in relation to the ‘Northern Africa’ emergency. Besides Manduria, three more centers whose profiling agendas differ yet again, emerge, i.e., the reception and identification centers (Cai, Centri di accoglienza e di identificazione) dotted around Southern Italy. We should also consider these briefly. Housed in the former Andolfato barracks in the province of Caserta, one of these structures was closed after a riot during the night of June 7 and 8, 2011. Another Cai resulting from this ‘Northern Africa Emergency’ is located in Chinisia, in the province of Trapani, in the area of a disused airport, with 90 tents housing 8 people each and surrounded by a fence to avoid escape. 70km from Potenza, in Palazzo San Gervasio, a ‘reception’ structure is improvised on a land confiscated from one of the Sacra Corona Unita bosses, a terrain surrounded by concrete walls and equipped inside with a sort of cage with nets over 5m high. The multiplication of centers’ typologies and modes of confinement produces a long series. On April 21, 2011, identification and reception centers (CAI) were normatively turned into temporary identification and expulsion centers, a permutation which clarifies the eminently securitarian profile of the ‘new sites’ created by the ‘Northern Africa emergency,’ a profile that was reiterated by the Monti government, when on Jaunary 28, 2012, a public ordinance extended the Santa Maria Capua Vetere and Palazzo San Gervasio operations until December 31, 2012. Finally, in July 2011, a new identification and expulsion center opened in Milo, with 204 places, occupied almost exclusively by Tunisians.

From dry land to the sea. The Berlusconi government also instituted floating identification and expulsion centers, sort of galleons (prison ships?) for the fast-tracked expulsion of Tunisian migrants. Returning to the date of September 23 when Lampedusa is declared an ‘unsafe heaven’ after a migrants riot and the subsequent lynching by some of Lanpedusa’s residents. In that situation, 700 Tunisians were put on board three different boats: Moby Fantasy, Audacity, and Mony Vincent. Tunisian migrants were detained for weeks in these prison boats off the Palermo pier, with a measure that allows restraint without the need of validation on the part of the judge.

These spatial confinements were supplemented with a temporal confinement. The extension to 18 months of administrative detention, decided by decree on June 16, 2011 and then ratified on August 1, 2011.

8. Struggles, Resistances, Escapes

Manduria, March 28th, April 2nd, and July 5th, 2011. Hundreds of Tunisians flee the detention centre of Manduria, in the province of Taranto. It is the first big escape by those Tunisians who formed part of the revolution, after the first riots in the detention centers of Restinco (February 3, 7 and 12, 2011) and Modena (February 27), and after a hunger strike in Turin (March 1). Manduria is a symbolic place when it comes to composing a chronology of struggles, resistances and escapes that takes into account ‘flight’ as practice which succeeded the revolution of spaces occurring in Tunisia, acting upon the proximity of the two shores of the Mediterranean. ‘The oxygen of freedom,’ is how it is defined by a Tunisian guy in the processing centre of Mineo who states that: ‘it is the possibility to travel like everybody else. This is reason why we left.’1 It is an intransitivity of freedom, acted upon by Tunisian migrants and which gave rise to a domino effect of events, acting as the catalyst for other struggles, and radicalizing other practices of resistance. On May 9, 2011, asylum seekers at the Mineo processing center block the state highway and start a hunger strike to protest against Territorial Commissions not processing their asylum claims. On August 1, 2011, rioting asylum seekers burst into the processing center of Bari Palese. They occupy the bypass and the railway, bringing the town to a standstill, while the police response results in fifteen injured. An insurrection of ‘gue- rilla migrants’ as the newspapers put it, also referring to the way in which events had been orchestrated. A few months later, in Decem- ber, 45 asylum seekers are indicted for the events in Bari. Meanwhile, day laborers in the Apulian village of Nardò go on strike to protest against the exploitation of migrant labor in tomato plantations. The strike, which started on August 1, 2011, goes on for ten days. These revolts by migrants of the Tunisian revolution functioned as catalytic forces within Italian space. They set in motion and multiplied a sequence of struggles and resistances across Italian territory, using different modes of operation such as hunger strikes, fires, flight and self-harm. The spread of struggles reached a peak between April – after the Italian government started deporting migrants to Tunisia again on 7 April – and June, 2011. This is a period of time when flight, arson attacks and protest action followed one another.

On May 24, 2011 more than 200 Tunisian migrants housed in the First Aid Centre of Lampedusa riot, chanting: ‘We want to go away from here [we want to leave].’ They start a hunger strike against their detention that had not been legally authorized. On April 17, 2011 a group of migrants, who had been waiting for days in the streets of the town of Ventimiglia for the right moment to cross over into France, finally get on a so-called ‘dignity train,’ together with Italian and French antiracist groups. This train ride functioned as a kind of ‘declared crossing’ yet one which came up against the reimposition of national borders by French Minister of the Interior, Claude Gueant, who stopped all trains from crossing the border in both directions.

In the space of a week, migrants escape twice from the detention center of Chinisia, in the province of Trapani. The first escape takes place on May 25, 2011, less than a week after the opening of the center and the second occurs on June 1 when 44 migrants succeed in escaping. On June 27, 2011 – ten days after the extension of the maximum period of detention to 18 months is approved in Italy – a revolt breaks out in the detention center of Modena. In this context 23 migrants manage to escape. It is also in this context that the press, for the first time, makes reference to ‘an external orchestration which facilitated the revolt and the escape.’

Between the end of July and the end of September, a second wave of revolts takes place. The continuation and the spread of struggles go hand in hand with their radicalization over the months. Struggles go from symbolic acts of resistance in March and April, 2011, when Tunisians climbed up onto detention centers’ roofs chanting ‘freedom, freedom,’ to escape attempts in the same detention centers, and direct confrontation with the police, as in the case of the riot at the Ponte Galeria center (Rome, July 29-30, 2011). The week before, de- portations of migrants were stopped due to revolts and frequent acts of self-harm by migrants. Many riots and escapes, in fact, took place as soon as migrants knew of an imminent deportation. This happened on August 23, 2011, when in the first aid and reception center of Pozzallo an apparent uprising of over a hundred detainees in the first aid and reception center of Pozzallo caused a diversion which allowed fifty-four to escape. After the blaze of the detention centre of Lampedusa (September 20, 2011) and the guerrilla attacks against migrants triggered by Lampedusa’s residents, governmental migration policies ‘answered’ with measures of extraterritorial detention in the form of prison ships.

Successful escapes were often the result of collective strategies of action, planned in advance and acted on by large groups. Turin, September 22, 2011. Thirty migrants escape during the night, having prepared holes in the perimeter fences days earlier. And the images of the first aid and reception center of Lampedusa burning and of the riots taking place in the other Italian detention centers, all support and strengthen the idea that it is possible to struggle and fight collectively. Both the riot in Turin and the one which took place in Ponte a Galeria on September 27, 2011 when sixty Tunisians escaped, constitute a prompt response to the special agreement on repatriations signed by Italy and Tunisia on September 19, which mandated one hundred repatriations per day. But where the Italian government considered the matter concluded with this extraordinary plan for repatriation, struggles continue, and in December 2011, three other riots and escapes take place – notable among these are the escape from the detention center of Vulpitta (December 14, 2011), the riots at the detention center of Turin (December 9, 2011) and those at the detention center of Bologna (December 17-18, 2011) where migrants set various parts of the center on fire before continuing their resistance through hunger strike.

However, revolts do not occur only in an Italian context. They also spread through the space at the border of Libya and Tunisia. In May 2011, asylum seekers at the refugee camp of Choucha in Tunisia, located six kilometers from Ras-Jadir, protest by blocking the only road connecting Libya and Tunisia three times, demanding resettlement elsewhere. In the wake of the protests, residents of the nearby Tunisian village of Ben Guerdane organize a raid in the camps and kill four Eritrean migrants. Acts of violence such as the one

perpetrated by the residents of Ben Guerdane are not isolated events. On February 28, 2012, the church of the camp is damaged by acts of vandalism, while the Tunisian army denies that the damage caused was intentional.

Finally, there is the resistance brought on by extreme grief. It is the struggle of mothers and families who, for months, have been beleaguering ministers, functionaries, secretaries and the appointees of European delegations visiting to sign agreements and pacts with Tunisia on the streets of the capital. They are the mothers and the families of missing Tunisian migrants, with their language of photos and the radical nature of their grief, a radicality that, from one shore to the other, suggests to us that these lives surely do matter.

9. Border Enforcement

Many types of borders were put in place against Tunisian migrants and asylum seekers coming from Libya by both individual European states and the EU. The beginning of the Frontex ‘Hermes Operation,’ on February 20, 2011, constitutes the date assigned to this icon. ‘Hermes,’ an operation of joint patrolling of the Sicilian Channel by EU and Italian forces, already planned for June 2011, gets put for- ward to February. Its initial expiry date (available for renewal) is fixed for March 31, 2011, with two million Euros allocated towards it. For border enforcement operations, Hermes deploys four planes, two boats, and two military helicopters. This equipment is provided by the six Member states taking part in the operation (Italy, France, Germany, Malta, Spain, and the Netherlands). The operation also con- stitutes Switzerland’s debut in a Frontex operation, with the deployment of a group of experts to take part in the mission. The operation also provides for a Europol mobile office on the Island of Lampedusa to assist with ‘operational analytical support,’ as it is referred to on the Frontex website. However, according to antiracist associations and activists working on Lampedusa island, the agenda of the Frontex operation is rather different and consists in gathering information to identify and deport migrants.

Starting from the end of February, 2011 the Sicilian Channel is jointly patrolled by Italy and Frontex. Before that date, however, when Italy alone was responsible for managing what it termed the ‘North Africa emergency,’ the Sicilian Channel, had turned into a Wild West of pursuits and gunshots. On February 15, 2011, the Italian military corps Guardia di Finanza intercepts a boat with Egyptian migrants on board and, when the boat tries to escape, Guardia di Finanza takes fire, leaving the boat captain injured.

In the meantime, the Mediterranean Sea is regularly traversed by European and Italian politicians, engaged in vertiginous diplomatic activity with the interim Tunisian government, with the aim of redrawing those European overseas borders which used to be very efficiently controlled under the regime of Ben Ali before being erased by the revolution. Following a visit to Tunisia around mid-February 2011, Catherine Ashton, High Commissioner of Foreign Affairs of the European Union, announces an imminent 17 million Euros fund- ing to the Tunisian government with another 258 million Euros anticipated for 2013. However, the journeys made by Italian politicians’ to Tunis mark intense and conflicting negotiations, in the attempt to reach a bilateral agreement for managing the alleged ‘immigration emergency.’ The website of the Italian embassy in Tunis reports nine official visits between January 2011 and the date of the signature of the agreement, on April 5, 2011, suggesting an arduous and drawn out negotiation process. The agreement signed in Tunis by the Italian Minister of the Interior Roberto Maroni and his Tunisian counterpart Habib Essid, establishes the financial and technical aid that Italy would provide in order to train Tunisian authorities to control their coasts and prevent migrant departures. In exchange, Tunisia committed to the implementation of repatriation measures according to a streamlined procedure targeting Tunisian migrants without residence permits arriving on the Italian coasts after April 5, 2011.

Moreover, April 5, 2011 is also a very significant date, since it delineates the ‘humanitarian border’ that Italy imposed upon Tunisian migrants establishing a path to a temporary residency permit for humanitarian reasons for those migrants coming ‘from North African countries’ who entered Italy between January 1, 2011 and midnight of April 5, 2011. This permit was the result of longstanding negotiations and met with resistance from the Tunisian government with respect to the wishes of Maroni, who probably intended to send all migrants arriving in Italy since January 2011 back to Tunisia. However, this temporary permit for humanitarian reasons came with an expiry date. Issued as a six-month permit, renewable up until March 2013, it was granted only if claimed within eight days from the day of the publication of the decree. But there was always another border blocking Tunisian migrants once they had got to Europe and were holding in their pockets both the temporary residence permit and the travel title valid for the Schengen, which the Italian permit provided for them.

The other big chapter of border enforcement operations involves the story of the border between Italy and France. French authorities engaged in intense raids preventing Tunisian migrants from entering France, pushing them back to Italy. On March 2, 2011 the new Interior Minister, Claude Guéant, outlines, after the arrest of about twenty migrants at the Italian border, his vision of the Arab Spring in relation to the European borders: ‘the quest for freedom that manifested on the Southern shore of the Mediterranean, presents France with two sets of responsibilities: guiding these peoples towards real democracy but also preventing uncontrolled waves of migration.’ Indeed, two days later, the Minister asked Italian authorities if they would retain Tunisian migrants who were trying to get into France on Italian territory, contending that the migration of these Tunisians was an economic migration and that French authorities were required to stop it. A requirement expressed through the re-establishment of massive controls at the borders with another EU member state, Italy, which produced the interruption of the regime of free circulation between signatory states of the Schengen Agreement. According to a note from the French Home Affairs Ministry, between February 23, 2011 and March 28, 2011, French authorities blocked 2,800 Tunisian migrants coming from Italy and, out of these, 1,800 were pushed back to Italy.

and Tunisia, and through raids and push-back operations at the Italy-France border), were instead vanishing and fuzzy when it started to be a question of establishing the competence of search and rescue interventions for helping migrant boats in distress at sea. The long-standing diatribe between Malta and Italy about the borders of the Search and Rescue (SAR) zone was indeed reactivated in the case of migrants coming from the Southern shore of the Mediterranean, with the usual conflicts over the jurisdiction of the rescue. Indeed, on many occasions the Italian Minister of the Foreign Affairs, Franco Frattini, protested or asked the Italian ambassador in Mal- ta to protest against Maltese authorities for their failure to rescue boats in distress at sea in Malta’s SAR zone. While Italian and Maltese authorities were fighting about the borders of their respective SAR zones, Tunisian migrants and migrants coming from the Libyan conflict were on those boasts, dying or at risk of dying at sea.

10. Expulsions

We chose the island of Lampedusa as the symbolic site for this postcard because the first deportation flight takes off from here, on April 7, 2011, carrying 30 Tunisian migrants. The deportation happens two days after an agreement was signed between Italy and the provisional Tunisian government that at the end of March countered Italy’s intention to deport all Tunisian migrants who arrived in Lampedusa at the beginning of 2011. According to the agreement, Tunisian migrants arriving in Italy by April 5, 2011 could apply for a temporary residence permit of six months, while those who arrived after that date had to be deported ‘in a straightforward way and according to a streamlined procedure,’ that is to say relying only on the identification of the consular authorities. But the choice of the place of Lampedusa in these ‘postcards of the revolution’ also alludes to the push back operation carried out by the Italian Military Navy, just a few miles from the coastline of Lampedusa, with the collaboration of the Tunisian Military Navy. 104 migrants were on the boat that gets pushed back, in clear violation of the principle of non-refoulement sanctioned by the Geneva Convention and by the European Court of Human Rights.

However, between April 7 and August 21, 2011 the deportation process doesn’t go on unimpeded and faces a number of interruptions. If during the month of April deportations seem a regular occurrence, with an average frequency of one flight per week from Lampedusa back to Tunis, on May 9, 2011, the flight taking off from Rome and headed to Tunis is prevented from landing by Tunisian authorities. The next day two deportation flights scheduled to take off from Lampedusa are cancelled. On May 17, 2011, the Italian government suspends deportations scheduled to depart from the airport of Palermo. The block goes on until June 3, 2011.

During the month of September, 2011 the mechanism misfires again. On September 16, a deportation flight that should have left from Palermo is blocked, while the flight departed from Milan disembarks with only 30 Tunisian citizens of a yet larger group – accord- ing to the Tunisian government this number corresponded to the maximum cap of permitted daily deportations. Tunisia resists pressure coming from Italy, despite having signed a special deportation plan, mandating, over the course of three weeks, a total of one hundred deportations per day for five days a week. The agreement was actually signed on September 12, 2011 by the Italian minister Roberto Maroni but was only made official on September 19. More specifically, it is after the fire at the detention center of Lampedusa (September 20, 2011)1 that deportations start to fail and Maroni declares that the agreement with Tunisia has fallen through. The riot in Lampedusa was indeed triggered by news concerning this deportation agreement reaching migrants detained in the center. However, the Italian government started deportation towards Tunisia quickly, right after engaging in extraterritorial detention measures, establishing prison-boats off the shore of Palermo. On September 23, 2011, 365 Tunisian citizens are deported. The total number reaches 605 in just three days, and in a week all Tunisian migrants detained on prison-boats are deported or, after further waiting onboard, are then transferred to de- tention centers on the mainland. This special deportation plan is officially declared as completed by the Italian government on October 25, 2011 with the last 50 Tunisians deported from Palermo airport. The number of expulsions of Tunisian migrants reached 1,490 after the signing of the agreement, and a total of 3,385 migrants were deported to Tunisia between April 7, 2011 and the end of October 2011.

11. Insistence on Space

What date and which place best represents the notion of an ‘Insistence on Space’? The insistence on space, a space, occurs at the moment of escape. It occurs when you get together with others in train stations, without a ticket; when you are blocked somewhere because ticket inspectors tell you to get off the train; when you go to the capital or some town or other in Italy to check out the atmosphere there; when you move on, assuming you have the option to do so. Or, the insistence on space, a space, occurs if there is someone who is waiting for you in France or in some other European country and when, as often happens, you realize you are being pushed back or that it is not so easy to insist on a space because Europe is not a smooth space and Schengen is not a country. You insist on space when you run out of money and you don’t know what to do. Insistence on a space where you may have a coffee, eat a sandwich, bathe, where you may find a mattress to sleep on instead of sleeping at the station, in a public garden or on the beach. But you insist on space also after the storm has passed, when the spotlights have been turned off and the struggles to occupy a place are over, when there is no longer someone to host you; when more or less close relatives or friends who were not waiting for you no longer know what to do with you and how to manage the fights with their husbands or wives due to your presence. You insist, then, in a less visible way, in small groups or only with certain friends. Insistences on space often take place by chance, through the grapevine. You are in Milan and you come back to Rome only because someone on the phone tells you to go there; you are in Bologna and you go to Ventimiglia, then you come back to some public garden in Bologna because at the police headquarters in Ventimiglia you are not given the residence permit. You stay on the beach for a few days, or in a garden, in the square in front of the station, in a squat with only the most trustworthy of travelling companions. You spend a number of weeks in Paris. But generally you stay in the street. This much is certain and often it’s not even easy to organize that. You start to get hungry, you smell and you only have one pair of jeans to wear. You never take your shoes off and your feet hurt. You call home, not too often, to let them know you are still alive but you do not speak of your insistence on space, and sometimes you start to think about returning. You even go as far as to insist on consulate offices to try to work out how to get home. But you burnt a border when you left on a boat, one that won’t allow you to burn it again on the return journey.

Where does this ‘Insistence on Space’ begin? What space of insistence requires annotating on the map? Rome, Palermo, Milan, stations, gardens, mosques, Paris, Ventimiglia, Marsiglia. We do not actually choose cities but we choose those places downtown that only those who insisted on space for a longer time, who refused to budge, got to know. Those who insisted on space for a shorter period, only got to know stations and gardens on the outskirts, various canteens or places in which to get changed, assuming these were not too difficult to find. To mark this icon ‘insistence on space’ on the map a number has been assigned to the city of Paris. We remain aware however that there were other streetabodes in numerous other Italian and French cities, as well as in the cities of other European countries. For some of those who insist, these places continue to be their street abodes. One only has to cast a glance about the subway to realize that those three or four guys wearing light jackets on a winter night are Tunisian migrants heading to some dilapidated shelter. It is Paris, but not exactly Paris: rather, it is the grass and the paths of the Parc de la Villette, where, as early as March and April 2011, the insistence on space was the most pronounced. It was here where people articulated their strategies for existence, dodging raids, joining forces with associations and other established collectives as well as inventing their own.

12. Occupations / Squats

« Le Collectif des Tunisiens de Lampedusa à Paris occupe depuis ce 1er mai à minuit l’immeuble appartenant à la mairie de Paris se situant au 51 avenue Simon Bolivar à Paris 19ème ». [The Collective of Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris has been occupying the building of the municipality of Paris, located in 51 avenue Simon Bolivar in Paris 19th neighborhood since May 1]. It is May 2, 2011 and this statement circulates on the websites of various French organizations, on social networks and on the mailing lists of different networks and associations. This is the way Tunisian migrants start to identify themselves in terms of the ‘Collective of Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris,’ a strange self-identification that provides collective terminology for both a citizenship and spaces of crossing and residence, regardless of their differences; a claim, in a sense, to a ‘European Spring’ for their existences. ‘A place of living together and self-organizing.’ A place for everyone. This is what the Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris demand in their first statement, after their occupation of the building in 51 Avenue Simon Bolivar on May 1, 2011. After the first raid by French police, about 250 people moved from Parc de la Villette, making their presence visible. Such a presence is described and affirmed at the end of their political statement. ‘We live in the street, we go 24, sometimes 36, hours without sleeping, we are scared, cold and hungry and we lack of all the basic things needed for an ordinary life. But despite these conditions we remain worthy.’ ‘We will stay here until a satisfying solution is offered to us. We demand the necessary documents to circulate and live freely.’ Yet in actual fact, they only ended up staying on Avenue Simon Bolivar for two days before being evicted by force by the police which led to a nomadic existence across Paris, occupying build- ings on the hills of Belleville: the college in Rue de la Fontaine-au-roi; a building in rue Bourdon, in Rue Bichat and near to the Tuni- sian embassy; the villa in Rue Botzaris, the French symbol of the dictatorship of Ben Ali, seat of the RCD (Rassemblement constitution- nel démocratique), the site of torture and an archive of many documents of the actions performed by the dictatorial apparatus. Then, June 16, 2011 and the final eviction arrives, followed by the nights spent at the Parc des Buttes Chaumont by those who had not found other solutions, and the dissolution of the movement. Over the course of six weeks, the ‘Tunisians from Lampedusa in Paris’ pursued their demand for karama [dignity] in the streets of Paris, surprised not to find themselves in the country of rights and freedom, and offended by the ways in which they were depicted by the mass-media and local authorities: as outlawed migrants, manipulated by a group of French anarchists – so the narrative went – hence deprived of their autonomy and awareness. They responded seriously in their statements where they referred to themselves as ‘the sons of the revolution’ and ‘mature and aware adults.’ They also answered with irony on banners at various demonstrations: ‘we made the democratic revolution,’ ‘we are here to help you do the same thing.’ After Paris, Padua, in Italy, where Tunisian migrants occupy the courtyard of a school from the May 24 to May 28, 2011, claiming this time a more institutional ‘right to asylum,’ playing with municipal and governmental decrees which had centralized the mechanism for asylum, placing it under the care of Civil Protection. But squats and occupations constitute a spatial takeover that cannot be limited to between the esplanades and the hills of Paris or in the courtyards of schools. This takeover proliferated this time with less noise, taking place within the folds of invisibility. It became visible again during the last few days of the summer of 2011. Here it was a case of tearing up the space, when in a squat in Pantin, in the area of Seine-Saint-Denis, in the morning of September 28 the bodies of six migrants – two Egyptians and four Tunisians – are found burned. The Tunisians had set off from the region of Tataouine, on the border with Libya, going through Lampedusa before finally arriving in Paris. They had been there for all of twenty days, with friends, before being burnt to death in a country boasting ‘liberty, equality and fraternity.’

13. Going back, Returns