Group show

April 13th – May 31, 2016

Espace Architecture Flagey-ULB, Brussels

Artistic curators: Isabelle Arvers and Nathalie Lévy

Scientific curators: Andrea Rea and Cédric Parizot

Coding and decoding the borders exhibits the work of artists and researchers who question the datafication and mathematization of the border. Over the past twenty years many actors (researchers, journalists, NGO workers and activists, elected politicians, employees of national administrations and of international organisations, and so on) have observed, documented, studied and sometimes even condemned the technological escalation at borders. Above the militarization of borders, the deployment of ever more sophisticated technologies (biometry, robots, fences and walls, integrated surveillance systems, data mining, big data, etc.) at state borders have been added to the traditional practices of control of movement of populations, goods, capital and information. The study of this technological escalation generally tends to separate the analysis according to the object of control: people, goods, capital. From a perspective intertwining art, research and expertise, the public is invited to look at the circulation of knowledge and techniques between these objects, at the functioning and dysfunctionning of the mechanisms of control as well as their circumvention by a multitude of actors.

The materiality of digital borders control

The escalation of border control on land, at sea, in the air and on internet in Europe and the rest of the world has radically transformed the nature of borders and how they operate. In order to adapt to and to follow the acceleration of movement of people, goods and information, control systems are relying on increasingly sophisticated digital technologies (biometrics, robots, integrated surveillance systems, data mining, etc.). Some analysts have seen in these trends the symptoms of the de-materialization of contemporary borders. Yet, all these control technologies still retain a strong materiality. They often rely on dense and heavy networks of physical infrastructures. While these networks can be sometimes hidden, like submarine cables (Submarine cable map, Markus Krisetya et al., 2016), they can also be staged such as walls, fences, and checkpoints (Cartographie des Murs, Stéphane Rosière et Sébastien Piantoni, 2016) in order to demonstrate state action and sovereignty. Both designed to manage human body and to be displayed, these artifacts contribute to the development of new esthetics of control (Body and Border, CoRS, 2016). Finally, border control technologies are all the more material as they instantiate or “materialize” hierarchies between people as well as the passage from one space to another (Immigration Game, Antoine Kik, 2016).

Antoine Kik, Immigration game, 2016

Stéphane Rosière et Sébastien Piantoni, Planisphère des barrières frontalières, 2016

Automation, Datafication and mathematization of border control

The automation of controls is accompanied by both the growing input of data and the “mathematization” of border procedures and border crossings. “Mathematization” is taken here to mean the progressive representation of borders in an increasingly abstract space, structured by quantitative methods (whether in economics, sociology, etc.), by autonomous information based on its own paradigms (logistics and the need for rapid and lower-cost border crossings) and by a specific form of language (technology as a corpus of knowledge on the techniques and tools of surveillance of persons and objects). Some people regard the automation and autonomization of border surveillance technologies as more reliable than human controls, others, on the contrary, express concern about this trend. They point to the risk of endangering the rights and freedoms of the mobile populations or states concerned. The artworks gathered in this part of the exhibition problematize this general trend. Banoptikon (Personal Cinema Collective, 2010-2013) reminds us of the datafication of the body and the new forms taken by control. SimBorder (Pierre Depaz, 2016) and eu4you (Larbits Sisters, 2015) highlight the centrality that algorithms have progressively taken in the control of people movements and access, while ADM8 (Rybn, 2016) shows their significance in the management of financial operations and flows.

Pierre Depaz, SimBorder, 2016

LarbitsSisters, eu4you, depuis 2015

Collectif Personal Cinema, Banoptikon, 2010-2013

RYBN, ADM8, 2016

Borders’ visibility

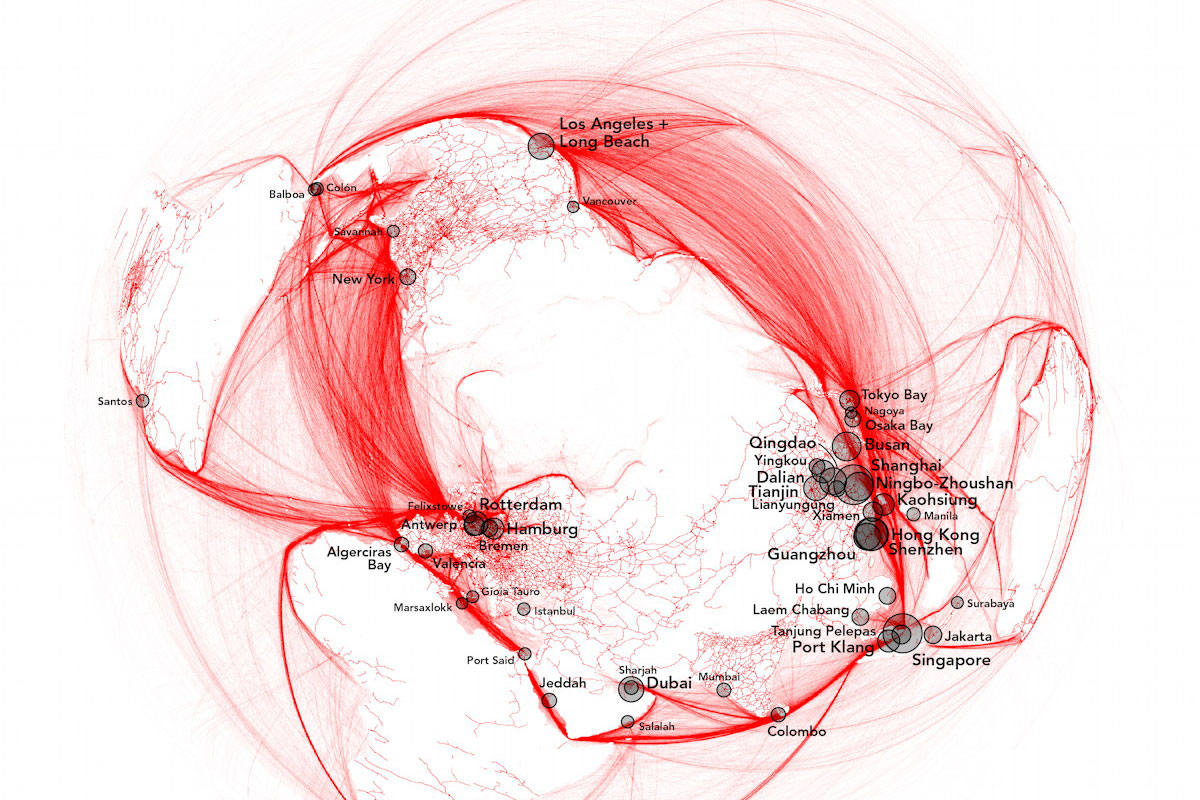

New technologies of information and communication have not only transformed the functioning of borders they have also changed borders’ visibility. They have introduced new apparatus through which we access and represent the world. Digital maps and GPS system have radically changed our perspective, the ways we project ourselves into space and thus the modalities by which we perceive and imagine borders. Moreover, data mining has not merely increased our calculation capacities, it has also invented a new world. While statistics had created society, and poll had produced public opinion, data mining has created digital traces, through which movements of people, goods, funds and information can be traced, monitored or displayed. Finally, by providing hightech mechanisms for the channeling, the facilitation or the filtering movements, these technologies help reorganize differently the space practices of different groups of populations within and around border zones. Drawing on photos (Calais 1, Michel Couturier, 2015), static and dynamic maps (The Migratory Red Mount, Nicolas Lambert, 2015; One World, Bill Rankin, 2015; Refugee’s trajectories, Martin Grandjean, 2015; 407 camps, Mahaut Lavoine, 2015; Parallel, Lawrence Bird, 2012), the artworks and research presented in this part of the exhibition problematize these very regimes of visibility. They also intend to render visible what is usually made invisible.

Lawrence Bird, Parallel, depuis 2012

Michel Couturier, Calais 1, 2015

Nicolas Lambert, The migratory red mound, 2015

Mahaut Lavoine, 407 camps, 2015

Martin Grandjean, Refugee’s trajectories, 2015

Bill Rankin, One World II, 2015

Critical documentaries

Most people build their knowledge on migrants’ lives and experiences through the press, reports and documentaries. While these media play a determinant role in informing and developing public awareness, the reality they construct and display is highly shaped by the narratives, standardized scripts and practices, as well as the regimes of visibility in which they are embedded. Our exhibition presents five critical documentary dispositives that aim to reflect on the very conditions by which contemporary and mainstream documentary practices gives us access and shape our representation of migrants lives and experiences. Nicola Mai’s ethnofiction Travel (2016) shows how migrants assemble their bodies and perform their subjectivity according to standardized humanitarian scripts of victimhood, vulnerability and gender/sex that act as ‘biographical borders’ between deportation and access to social support, legal documentation and work. Keina Espineira’s Colour of the Sea (2015) reflects on how performing a film in the threshold stage within the journey of subsaharian migrants contributes to produce and activate a specific border experience. Through a series of photos Giovanni Ambrosio (Please do not show my face, 2013) and a video Antoine D’Agata (Odysseia, 2011-2013) problema

Antoine d’Agata, Odysseia, 2011-2013

Giovanni Ambrosio, Please do not show my face, depuis 2013 (projet évolutif)

Isabelle Arvers, Heroic Makers vs Heroic Land, 2016

Keina Espiñeira, The Colour of the Sea. A Filmic Border Experience in Ceuta, 2015

Nicola Mai, Travel, 2016

Dysfunctioning and re-appropriations

Border control technologies are often considered to be omnipotent, omniscient et omnipresent. Both their promoters and opponents are fascinated by their power. Yet, they overlook the fact that it is not possible to dissociate surveillance techniques, however successful and automated they may be, from the political, social and economic conditions in which they are first designed then put into effect. Deployed and associated with systems of pre-existing checks and with specific institutional and political stakeholders, they reproduce the contradictions and lack of foresight of the organizations and stakeholders that deploy them. Moreover, in transforming and modifying the organizational environment in which they are deployed and in modifying the reality they are intended to control, they create new challenges. Lastly, they are often re-appropriated not only by the actors who implement them but also by those seeking to elude border surveillance. Border Bumping (Julian Oliver, 2012) exemplify the disruptive power of cellular telecommunications infrastructure that often challenge the integrity of national borders. Virtual Watchers (Joana Moll, Marius Pé and Ramin Soleymani 2016) highlights both the dysfunctionning and the unforeseen re-appropriations of a panoptic system of surveillance by American citizens along the border with Mexico. Cartographies of Fear #2 (Anne Zeitz et Carolina Sanchez Boe, 2016) questions how by taking over technologies of communication, migrants can affect their relationship to space. Finally, Borderland Biashara & Mobile Technology (Emerging Futures Lab, 2015) highlights and maps the way the reappropriation of mobile phone technologies contribute to sustain an informal economic ecosystem in the borderlands of East African communities.

Emerging Futures Lab (EFL), Borderland Biashara & Mobile Technology, état des recherches en 2015

Anne Zeitz et Carolina Sanchez Boe, Cartographies of Fear #2, 2016

Joana Moll et Cédric Parizot, The Virtual Watchers, 2016

Julian Oliver, Border Bumping, 2012

Partnership

Faculté de Philosophie et Sciences sociales de l’Université Libre de Bruxelles, l’Organisation Mondiale des Douanes, l’antiAtlas des frontières, l’Institut de recherches et d’études sur le monde arabe et musulman (CNRS/Aix Marseille Université), le projet LabexMed (Aix Marseille université, Fondation Amidex), le Laboratoire d’Economie et de Sociologie du travail (CNRS/Aix Marseille Université), PACTE (CNRS/Universités de Grenoble), Kareron et l’Ecole supérieure d’Art d’Aix en Provence.